A shared political vernacular and slang has developed among Taiwanese youth activists in recent years, serving as the basis for many of the Internet memes about politics which are circulated among young people on social media, and providing the visual language for much of artistic production which sprung up around the Legislative Yuan occupation during the Sunflower Movement.

The following is “A” to “E” in an alphabetical dictionary of some of the terms frequently used by activists, accompanied by artistic depictions from the Sunflower Movement or preceding movements, along with some of the protest chants or memes which sprung up during the movement itself. This is put together along with documentation of the artwork produced during the Sunflower Movement, seeing as it was deeply rooted in this activist vocabulary and not so easy to parse out from it. This name, “Rioter’s Dictionary”, comes from “baomin” (暴民) or “rioter”, a term that Taiwanese youth activists jokingly refer to themselves as.

An Age Of Collapse

“An Age of Collapse” (崩潰時代) is phrase used to describe Taiwan’s present conditions, especially for young people, in which opportunities for Taiwanese young people seem to have largely disappeared because of lagging economic conditions, an inability to compete with China, and a deterioration of Taiwan’s political freedoms because of Chinese influence. As such, young people are “losers” (魯蛇) living in an “age of collapse” in which they have no hope. Yet the eventual rise of the Sunflower Movement proved rupturing of such notions. The phrase originally came from a 2011 publication by labor groups and academics.

Photo credit: Charlie Chang/Flickr/CC

Anime-influenced Artwork/Memes

Perhaps reflective of strong cultural influence on Taiwan from Japan, anime-style art was a common aesthetic of artwork at the Legislative Yuan encampment. These ran the gamut from anime-style personifications of Taiwan, usually as female, the use of virtual idol Hatsune Miku to call for support of the movement, to depictions of Taiwan in line with popular anime Hetalia: Axis Powers, which depicts WWII-era countries in personified form. Boy’s love (yaoi or BL) art of depicting fantasized romantic trysts between prominent movement leaders was a genre itself, something referred to as “hehe.”

Photo credit: Charlie Chang/Flickr/CC

Other times, artworks featured reference to popular anime such as One Piece or Attack on Titan. Leading figures of the Sunflower Movement were sometimes depicted in line with the protagonists of these works, maybe a way in which Sunflower Movement participants heroicized themselves in line with fictional works they enjoyed. Sometimes this involved not just anime, but the use of imagery appropriated from popular movies. References to Japanese TV dramas also appeared–for example, the site where free coffee was distributed in the encampment had a sign tacked above it reading “Midnight Kitchen” in reference to the popular Japanese TV drama of the same name.

At least two books of Japanese-style manga about the Sunflower Movement was later produced by Taiwanese manga artists.

Hatsune Miku artwork. Photo credit: Charlie Chang/Flickr/CC

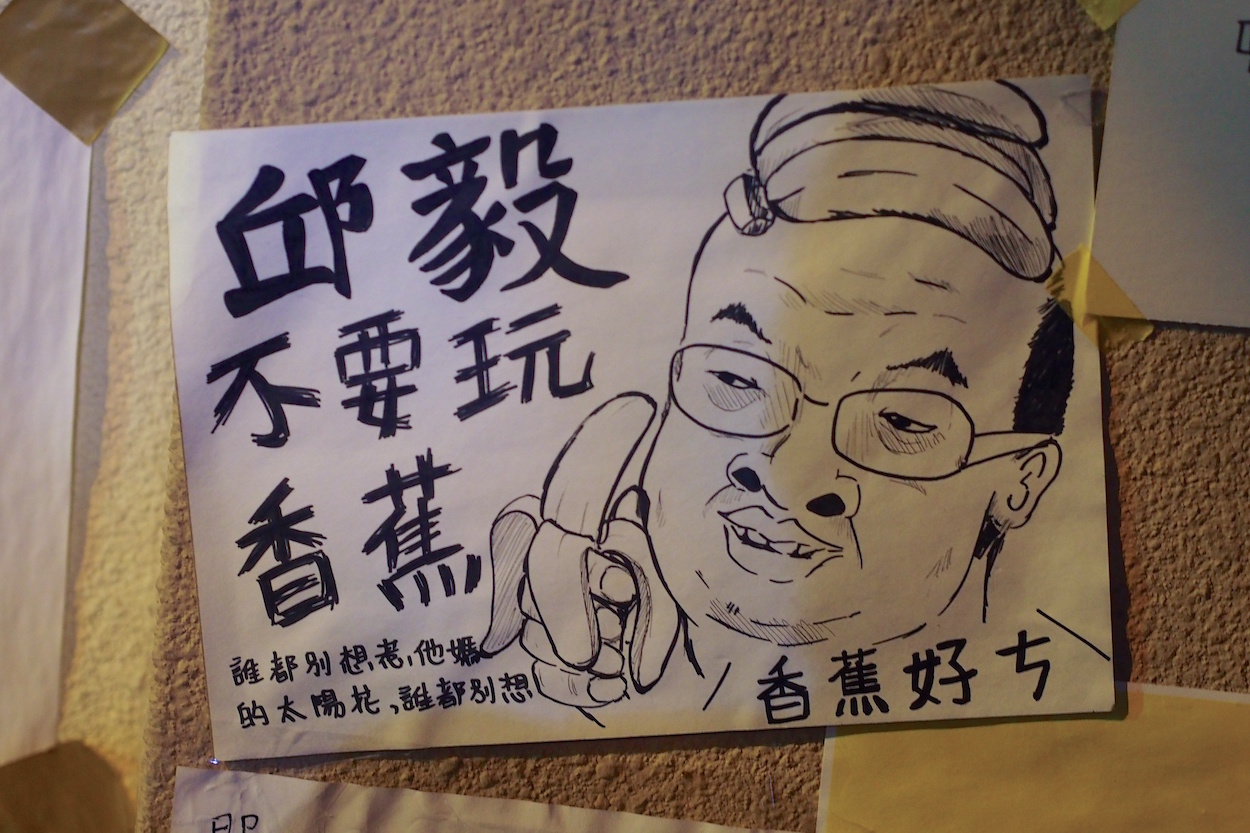

Bananas

After former KMT legislator Chiu Yi (邱毅) mistook the name of the movement for the “Banana Movement”, banana-themed artwork subsequently appeared frequently at the Legislative Yuan as a meme. A baker in Chiayi subsequently made and began selling a sunflower-themed banana cake, the name of the cake being a pun on Lin Fei-Fan’s (林飛帆) name.

Photo credit: Charlie Chang/Flickr/CC

Birdcage Referendum Act

Because of criticism that the conditions of the Referendum Act needed to hold a public referendum in Taiwan are too high, the Referendum Act is sometimes referred to as the “Birdcage Referendum Act” (鳥

Art installation featuring animals in cages. Photo credit: 綠魚/Flickr/CC

Black Box

Seeing as the movement was opposed to the “Black Box” (黑箱) of how the CSSTA was passed, the black box also became a common feature of occupation art.

Photo credit: Charlie Chang/Flickr/CC

Bone-sucking Tribe

Alongside criticisms of young people as the soft “Strawberry Tribe” (草莓族), young people are derided as a “bone-sucking tribe” (啃老族) which returns home to suck on the bones of their parents, in terms of being supported by their parents because of an inability to find jobs on their own and establish their own lives.

Photo credit: Abby Chen/Flickr/CC

Capitalism/Greed/Selling Out Taiwan

Given the perception that the Ma administration was selling out Taiwan to China, much artwork in the Sunflower Movement encampment, sometimes criticizing the Ma administration for its greed. Some artwork was more directly critical of free trade or capitalism, much of which came from the Untouchables’ Liberation Area.

Photo credit: Charlie Chang/Flickr/CC

Chiang Kai-Shek

Seeing as Chiang Kai-shek (蔣中正) is hailed as the founding father of the ROC, even if he was also the perpetrator of Taiwan’s authoritarian period, it is not surprising that much artwork during the movement used Chiang as a symbol for what was opposed by student demonstrators or otherwise mocked Chiang. In particular, following the Sunflower Movement, it became a hotly debated issue as to what should be done with Chiang statues located all across Taiwan, oftentimes on university campuses. In the years preceding the Sunflower Movement, however, it had become popular among campus-based student activists to deface Chiang statues in creative and imaginative ways, such as making a Chiang statue into a statue of a robot or a Super Sentai superhero.

Photo credit: Brian Hioe

Cheng Nan-Jung

“Nylon” Cheng Nan-Jung (鄭南榕), the “Father of Free Speech in Taiwan” and a staunch advocate of Taiwanese independence, was the publisher of Freedom Era Weekly (自由時代周刊) during the martial law period. Chen became a martyr of the democracy movement who self-immolated himself after a stand-off with police that lasted several weeks in Freedom Era Weekly‘s offices. Chen was invoked many times by students during the movement as an inspiration in his willingness to sacrifice himself for the sake of Taiwanese democracy and memorial ceremonies commemorating the anniversary of his death were held during the movement.

Photo credit: Duke Lin/Flickr/CC

China Factor

The “China Factor” (中國因素), a phrase coined by sociologist Wu Jieh-Min (吳介民), is a term used to refer to China’s undue influence on Taiwanese politics, using its economic weight in order to compel Taiwan to its will. This would often be with the aid of KMT elites who may not only identify with China, but have a number of overseas business interests spanning Taiwan and China, meaning the political reunification of Taiwan and China would be advantageous to them and they would not be affected either way.

Photo credit: Charlie Chang/Flickr/CC

Citizens

In line with the non-violent discourse of the Sunflower Movement and the emphasis on peaceful civil disobedience, demonstrators oftentimes referred to themselves as “citizens” (公民). In this sense, movement participants sometimes justified their political participation as founded upon the basis of their being “citizens” who had a say in the actions of their government rather than disorderly rioters, or that participation in the movement was even a form of civic responsibility as a citizen. At the same time, organizers sometimes would refer to themselves as “rioters” (暴民) in order to buck such notions of civic respectability.

Photo credit: Charlie Chang/Flickr/CC

Civil Disobedience VS 革命ing

The popularity of the slogans “civil disobedience”(公民不服從) and “革命ing” (revolution-ing) within the movement is reflective of how participants in the movement understood their actions in a multifaceted way. On the one hand, revolution evokes a sense of power, perhaps, in the sense that demonstrators understood their actions as drastic in nature and even revolutionary, although this may also simply be radical chic. On the other hand, civil disobedience would suggest that violence, as in suggested by the word for revolution in Chinese (革命), which literally means “to end a life”, is far from off the table and that all that was aimed for by the movement was peaceful nonviolent demonstration–even then, however, there is the sense that this is a powerful act of rebellious defiance. Perhaps, then, can we understand how activists felt self-empowered in their actions.

Photo credit: Charlie Chang/Flickr/CC

Coffee Shops

With the sheer amount of coffee shops which exist in Taipei opened by young people, some take this as a sign that young people today as all “hipsters” or wenqing (文青). But it may be that lack of opportunities have led to opening coffee shops to become one of the few viable forms of entrepreneurship, given that there may not be any other viable options with guaranteed income. Sometimes establishing coffee shops were attempts to create cultural centers as well, particularly in the case of young people who moved to the country side to support efforts of Taiwan’s rural movement.

Photo credit: 中岑 范姜/Flickr/CC

Come! Come! Come! Come!

“Come! Come! Come! Come!” (來來來來!) was a meme which resulted from when gangsters that came with “White Wolf” Chang An-Lo during his visit to the Legislative Yuan on April 1st, with several hundred gangsters in tow, attempted to provoke students into fighting with them. One gangster in particular, who later became known as “Come Come Brother” (來來哥) began shouting ”You come! Come! Come! Come! … Come! Come! Come! …Come! Come on! Come on!“ (你來來來…來來來…你來啊、來啊!), “Come! Come! Come! Ah, come! Come! Come! Come!” (來來來阿來來哩來來阿哩來來來來) and similar phrases at students, leading to much mockery.

Photo credit: Abby Chen/Flickr/CC

Cosplay

Cosplay was in the movement sometimes a way for individuals to lighten the mood of protests. Lai Ping-Yu (賴品妤), a prominent leader of the Black Island Youth Front, was, for example, known for dressing up as anime characters at protests. Another individual was a man or sometimes woman seen wearing a leopard costume, with a parrot puppet, seen at demonstrations ranging from anti-nuclear rallies to labor protests, presumably hoping to lighten the mood of protests. Others would dress up for the sake of performance art in the encampment.

Photo credit: Abby Chen/Flickr/CC

Dibao

Dibao (帝寶), also known as The Palace, is a luxury apartment complex in Taipei considered one of, if not the most expensive luxury apartment complex in all of Taiwan. Prominent political figures of a pro-China bent and wealthy oligarchs such as Sean Lien reside in Dibao. Particularly in an era in which housing increasingly unaffordable for young people, with many having given up hopes of ever owning a house, and in which real estate prices across Taiwan, especially in Taipei, are on the rise, Dibao became an emblem of oligarchical rule by the wealthy in Taiwan.

Photo credit: Charlie Chang/Flickr/CC

Everyday People Participating In Politics

“Everyday people participating in politics” (素人政治) was a slogan which became representative of the way in which the participants of the Sunflower Movement were political amateurs, who were engaging in politics through their actions, but did not have any experience whereas politics usually seems like it is in a lofty domain far removed from the lives of everyday people. This phrase later became a prominent refrain of Ko Wen-Je’s (柯文哲) campaign for Taipei mayor, since Ko was an individual with no prior experience politically, who ran as an independent rather than as a candidate of either the DPP or KMT.

Photo credit: Tinru/Flickr/CC

Eyes

Artwork depicting eyes, suggesting that instead of the government watching the people in an all-powerful fashion a la 1984, the people were instead watching over and providing oversight over their government, were commonplace in the occupation encampment.

Photo credit: Charlie Chang/Flickr/CC

The Rioter’s Dictionary: